The Apothecary in Colonial America

The apothecary, like other medical specialities, struggled for autonomy and increased scope of practice against the rigid guild system in place since medieval times. During the age of discovery, immigrating to the American colonies afforded more freedom to practice one’s craft. Exploring the progress of the apothecary in both the English and Spanish colonies of North America provides insight into the evolution of the modern pharmacy profession.

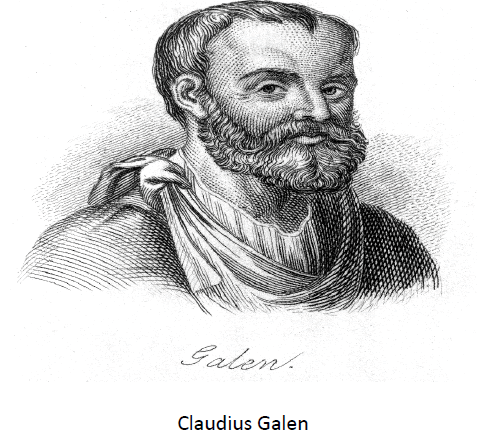

The Galenic and Paracelsian Approach to Medicine

The dominate theory of disease was still heavily influenced by Claudius Galen’s four humors; blood, phlegm, yellow bile and black bile [1]. The Persian scientist, Abu Al Sina (Avicenna), added an elemental facet to the four humors including: air, water, fire and earth. It was largely believed that humoral imbalance was the root of all disease.

Paracelsus (1493-1541) rejected the humoral theory and instead favored a more chemical approach using minerals and metals [2]. Paracelsus was also an advocate of the “doctrine of signatures.” The doctrine of signatures was a theory that if a plant looked like a human organ it would be of therapeutic value in treating an illness of that particular structure. It is fair to say that apothecaries of the American colonies and Europe used a mix of both theories in their individual medical practice [3].

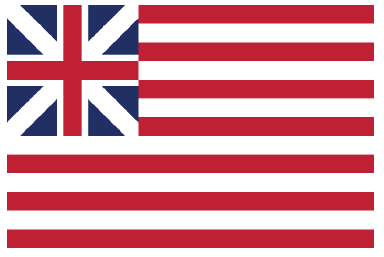

British Colonial America

From medieval times until the 17th century, the apothecary profession fell under the jurisdiction of the Grocers’ Company. This powerful guild included spicers, pepperers, and shopkeepers. Apothecaries struggled under this system to have any measure of independence despite having the large responsibility of caring for the sick poor [4].

In 1617, royal apothecary, Gideon de Laune, founded the Worshipful Society of Apothecaries; this event was pivotal in elevating the status of the entire profession. This society was self-governing, implemented apprenticeships regulations, and set quality of standards for medications sold [5]. Apprenticeships, under the Worshipful Society guidelines, were required to be seven or eight years in length with mandatory education in chemistry, Latin, and botany. As this society grew in influence, so did the animosity with physicians over the apothecaries expanding scope practice.

It was common for surgeons to also be an apothecary, especially in rural areas of Britain and colonial America [6]. Colonial America did not adhere to the rigid class structure of England; medical practitioners of all varieties were in great demand. It should be noted that fraud did exist among physicians, surgeons, and apothecaries who were unqualified to practice their trade, but did so anyway for financial gain.

Medication Preparation and Therapeutic Uses

Treatment of diseases strongly reflected upon the Galenic principles of restoring humoral balance. Remedies that induced vomiting, sweating, and salivation were popular along with blood letting. The apothecary was well versed on medications to induce the remedies mentioned above and how to prepare them.

Medications could be categorized into the following classes with some examples of each:

Anodynes- (pain relievers)- Opium,

Emetics- (produced vomiting)- ipecac (Ipecacuanha),

Anti pyretics- (fever reducers)- White Willow Bark (Salix Alba),

Cathartics- (laxatives)- Jalap Root (Ipomaea jalapa),

Diaphoretics- (sweat producing)- Mercury.

The apothecary could prepare remedies in various different ways, some of the most common being:

Pills- Dried herbs or powdered compounds mixed with either wax or honey,

Salves-Medicinal compounds mixed in lard for topical application,

Poultices- Moist herbal mixture applied to skin to reduce inflammation,

Tinctures-Concentrated liquid herbal extracts dissolved in alcohol,

Infusions- Leaves and flowers steeped in hot water,

Decoctions- Roots and bark simmered in boiling water [7].

Notable Colonial Apothecaries

The increased freedom to practice the apothecary trade in the colonies gave way to the rise of the first female apothecary in the 1720’s, Elizabeth Gookin Greenleaf (c.1681-1763). She was the wife of a New England physician and minister and regularly prepared medicines for his parishioners.

Zabdiel Boylston

• Dr. Zabdiel Boylston (1679-1766) was an innovative Surgeon-Apothecary that is credited with championing the cause for inoculation to combat the smallpox epidemic of the 1720’s. Inoculation was a controversial of issue of the period [8].

Hugh Mercer

• General Hugh Mercer (1726-1777) was a Scottish Surgeon-Apothecary and a decorated veteran of the French and Indian War. He was a close friend of George Washington and lost his life after the Battle of Princeton in 1777 during the American Revolution.

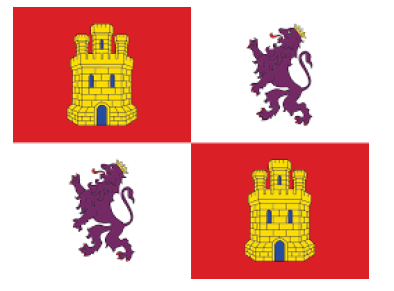

The Spanish Empire in the New World

The golden age of the Spanish Empire began with the marriage of royal cousins Ferdinand of Aragon and Isabella of Castile in 1469 [9]. This union brought stability to the kingdom, which gave way to an era of exploration and colonization of the New World. The Spanish found not only wealth in the form of gold and silver, but also in new medicinal plants from the Americas. The Spanish Monarchy was concerned with the public of health of its empire, and sent physician-botanists along on expeditions in search of new remedies.

Dr. Diego Alvarez Chanca

A physician from Seville, joined Christopher Columbus on his second voyage to the island of Borinquen (modern day Puerto Rico), where he described in great detail the vegetation of this exotic location and collected samples to study [10]. The use of chili peppers (Capsicum annuum) for both nutrition and medicinal purposes by the indigenous tribes was of interest to Dr. Chance, and was brought back to Spain.

Dr. Francisco Hernadez (1517-1587)

Francisco Hernadez was a personal physician and botanist to King Philip II and was tasked with the challenge of recording all the plants and animals of the New World. He is largely regarded as one of the fathers of natural history for his work [11].

The Royal Protomedicato

The protomedicato was board of physicians appointed by the Spanish Crown to regulate all medical professions in Spain and its colonies. The protomedicato was implemented in 1477 by Ferdinand and Isabella. The apothecary was under the jurisdiction of the royal protomedicato along with physicians, surgeons, and bonesetters; this governing body set standards for licensing and quality of practice [12]. The qualification criteria for an apothecary was as follows: must be male, had to be at least 25 years of age, apprenticeship experience required to be 4 years in length with proficiency in Latin, and needed a notarized certificate of apprenticeship completion by the regional magistrate. The development of a standardized pharmacopeia to be used by all apothecaries and physicians alike was instituted in 1739 with the Pharmacopeia Matritensis [13]. The protomedicato officials, with no advanced warning, subjected apothecary shops to yearly inspections to ensure that medicinal quality standards were being met. While the protomedicato was extremely powerful, enforcing these policies in the more remote aspects of the empire was problematic and fraud did take place.

Spanish Pharmaceutical Trade

The Spanish Crown dominated and exploited the market on medicinal plants from the Americas well into the 18th century [14]. Spanish pharmaceutical imports were found in medicine chests around the globe from Europe to Asia due to the effectiveness of the New World remedies. It is interesting to note, that despite the European politics, Spanish medicines were widely welcomed into the markets of allies and foes alike.

The most in demand Spanish medicines included but are not limited to the following:

Cinchona (Peruvian Bark)- contains quinine and used to treat malaria,

Guaiacum officinale (holy wood)- used to treat syphilis,

Smilax ornata (Sarsaparilla)- a “blood purifier” used to treat syphilis,

Ipomoea jalapa (Jalap Root)- used to relieve constipation [15].

Cinchona (Left) and Sarsaparilla (Right).

Conclusion

The apothecary profession saw tremendous progress from medieval times throughout the later 18th century. The scientific contributions of this profession are extremely significant with sixteen elements discovered by five apothecaries between 1750- 1803 [16].

Apothecaries, in many ways, provided care as much or more often than their physician counterparts and contributed to the development of medical care in both Europe and America.